Logic and Reasoning

Logic

“And concerning you, my brethren, I myself also am convinced that you yourselves are full of goodness, filled with all knowledge and able also to admonish one another. But I have written very boldly to you on some points so as to remind you again, because of the grace that was given me from God,” (Romans 15:14–15, NASB95)

Utility of Logic

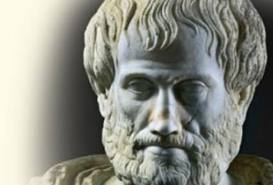

Logical argument, the rules of logic, and the history of logical argument enables rational discourse on thoughts of God and theology. Christ came to earth at an interesting time. Trade routes and the Roman network of roads made taking of the gospel to the world possible as never before. God clearly worked to prepare the way for Christ in the affairs of men, even in the world outside His chosen people. God worked in coordinated fashion through nations and men before, during and after His incarnation. Several hundred years before Christ came to earth, major contributions toward the preparations for Christ’s coming were made by Greece’s giants of intellect. Socrates, Plato and Aristotle developed reasoning, thought, argument and logic in a way that allowed man to think and communicate thoughts and concepts as never before. The Holy Spirit and the Apostles recognized and used this well-developed and well honed framework in their writings. The classic structure of logic was used not only in Christ’s time, Aristotelean logic is still used today in science, philosophy, and nearly all other “-ologies” at universities and centers of thought around the globe (albeit “refined” in some respects). In our culture today logic is often lacking, incorrectly applied, or even forsaken altogether; but the framework of logic has not been replaced with anything better. The classical framework of logic is still a useful tool in understanding and communicating truth. This framework provides the foundation for discourse on this blog. Logic is not a goal, not a product, not an end — but a means to the end goal. Logic is only a scaffolding, a means to accomplish the desired goal which is clearly understood thoughts of finite men about the infinite God. Logic has been called “the grammar of thought.” Grammar is language’s system of principles and rules which allow language to perform its function, communication. A great achievement of the ancient Greeks was development of a logic framework of principles for valid reasoning, inference and demonstration that has been in use since Hellenistic times. The accomplishment of Roman road builders was astounding, immense and long-lived. The works of Greece’s giants of intellect were similarly astounding and still stand, as useful today as when they were first fashioned.

God clearly worked to prepare the way for Christ in the affairs of men, even in the world outside His chosen people. God worked in coordinated fashion through nations and men before, during and after His incarnation. Several hundred years before Christ came to earth, major contributions toward the preparations for Christ’s coming were made by Greece’s giants of intellect. Socrates, Plato and Aristotle developed reasoning, thought, argument and logic in a way that allowed man to think and communicate thoughts and concepts as never before. The Holy Spirit and the Apostles recognized and used this well-developed and well honed framework in their writings. The classic structure of logic was used not only in Christ’s time, Aristotelean logic is still used today in science, philosophy, and nearly all other “-ologies” at universities and centers of thought around the globe (albeit “refined” in some respects). In our culture today logic is often lacking, incorrectly applied, or even forsaken altogether; but the framework of logic has not been replaced with anything better. The classical framework of logic is still a useful tool in understanding and communicating truth. This framework provides the foundation for discourse on this blog. Logic is not a goal, not a product, not an end — but a means to the end goal. Logic is only a scaffolding, a means to accomplish the desired goal which is clearly understood thoughts of finite men about the infinite God. Logic has been called “the grammar of thought.” Grammar is language’s system of principles and rules which allow language to perform its function, communication. A great achievement of the ancient Greeks was development of a logic framework of principles for valid reasoning, inference and demonstration that has been in use since Hellenistic times. The accomplishment of Roman road builders was astounding, immense and long-lived. The works of Greece’s giants of intellect were similarly astounding and still stand, as useful today as when they were first fashioned.

Aristotle’s logic, especially his theory of the syllogism, has had unparalleled influence on the history of thought. His teachings on logic did not always hold this position: in the Hellenistic period, Stoic logic, including the work of a man named Chrysippus who was born 105 years after Aristotle, enjoyed widespread popularity. However, in later antiquity, more than a century after Aristotle’s death and following the work of Aristotelian Commentators, the advantages of Aristotle’s logic became evident and dominant. Aristotelian logic was what was transmitted to the Arabic and the Latin medieval traditions. The works of Chrysippus have not even survived.

Aristotle’s logic, especially his theory of the syllogism, has had unparalleled influence on the history of thought. His teachings on logic did not always hold this position: in the Hellenistic period, Stoic logic, including the work of a man named Chrysippus who was born 105 years after Aristotle, enjoyed widespread popularity. However, in later antiquity, more than a century after Aristotle’s death and following the work of Aristotelian Commentators, the advantages of Aristotle’s logic became evident and dominant. Aristotelian logic was what was transmitted to the Arabic and the Latin medieval traditions. The works of Chrysippus have not even survived.

This is a remarkable and unique historical position given that one man, Aristotle, basically created the discipline in his spare time. Aristotle of course benefited from his fellow Greeks and predecessors Pythagoras, Socrates, and Plato. Kant believed that Aristotle had discovered everything there was to know about logic. Prantl, a historian of logic, suggested any logician after Aristotle who said anything new was confused, stupid, or perverse. During the rise of modern formal logic following Frege and Peirce adherents of Traditional Logic (the descendant of Aristotelian Logic) and the new mathematical logic often saw one another as rivals. However, recent work has demonstrated that application of techniques of mathematical logic to Aristotle’s theories reveal great similarities and overlap between Aristotelian and modern logicians.

The influence of Traditional Logic over the period preceding, contemporary, and following Christ’s time on earth is just one of many reasons to utilize Traditional Logic’s framework when seeking to understand the teachings of Christ, the God of the Bible, and spiritual truth.

Glossary of Aristotelian Terminology

- Accept: tithenai (in a dialectical argument)

- Accepted: endoxos (also ‘reputable’ ‘common belief’)

- Accident: sumbebêkos (see incidental)

- Accidental: kata sumbebêkos

- Affirmation: kataphasis

- Affirmative: kataphatikos

- Assertion: apophansis (sentence with a truth value, declarative sentence)

- Assumption: hupothesis

- Belong: huparchein

- Category: katêgoria (see the discussion in Section 7.3).

- Contradict: antiphanai

- Contradiction: antiphasis (in the sense “contradictory pair of propositions” and also in the sense “denial of a proposition”)

- Contrary: enantion

- Deduction: sullogismos

- Definition: horos, horismos

- Demonstration: apodeixis

- Denial (of a proposition): apophasis

- Dialectic: dialektikê (the art of dialectic)

- Differentia: diaphora; specific difference, eidopoios diaphora

- Direct: deiktikos (of proofs; opposed to “through the impossible”)

- Essence: to ti esti, to ti ên einai

- Essential: en tôi ti esti (of predications)

- Extreme: akron (of the major and minor terms of a deduction)

- Figure: schêma

- Form: eidos (see also Species)

- Genus: genos

- Immediate: amesos (“without a middle”)

- Impossible: adunaton; “through the impossible” (dia tou adunatou), of some proofs.

- Incidental: see Accidental

- Induction: epagôgê

- Middle, middle term (of a deduction): meson

- Negation (of a term): apophasis

- Objection: enstasis

- Particular: en merei, epi meros (of a proposition); kath’hekaston (of individuals)

- Peculiar, Peculiar Property: idios, idion

- Possible: dunaton, endechomenon; endechesthai (verb: “be possible”)

- Predicate: katêgorein (verb); katêegoroumenon (“what is predicated”)

- Predication: katêgoria (act or instance of predicating, type of predication)

- Primary: prôton

- Principle: archê (starting point of a demonstration)

- Quality: poion

- Reduce, Reduction: anagein, anagôgê

- Refute: elenchein; refutation, elenchos

- Science: epistêmê

- Species: eidos

- Specific: eidopoios (of a differentia that “makes a species”, eidopoios diaphora)

- Subject: hupokeimenon

- Substance: ousia

- Term: horos

- Universal: katholou (both of propositions and of individuals)

Discussion